TechCrunch recently featured a graph of Amazon’s acquisitions, ordering them by price, noting that the Whole Foods acquisition was extremely large compared to other ones Amazon has performed. However, the Whole Foods purchase is on a whole different ballgame.

The first point of comparison is that Whole Foods, unlike the other purchases Amazon has done, is a publicly traded corporation. This has two implications. First, the purchase price is not wholly up to Amazon; they have to buy it as a function of a premium of the share price, which they did. Second, we have SEC filings for it. We do not have the same level of access into Amazon’s other purchases, but scouring various Amazon SEC filings I have prepared a best guess at what those pre-acquisition financials might have looked like. I have gone down the acquisition price list and tried to suss out the financials, removing any companies I could not get solid data on.

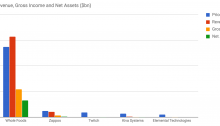

The below chart is compiled on the basis of purchase price, revenue, gross income (revenue less cost of sales, but not including salaries), and net assets (assets less liabilities such as loans). I’ve chosen these metrics in part because they are reasonably simple to establish, and in part because they show the potential for the operation. A company with a good gross margin can be made profitable; one without has not realised its business case well.

What becomes immediately evident is that of Amazon’s purchases, the tech acquisition ones follow the usual tech pattern; buying a company at a huge premium with little to no revenue, no profit and no real assets above and beyond the IPR and trademarks. Zappos and Whole Foods, Amazon’s largest acquisitions, fall into a different bucket. Both are profitable firms with established revenue streams, and the “premium” paid is, in fact, not that big compared to their revenues or gross profit.

It is not unreasonable, all things being equal, to take a company with a decent gross profit, and think you can improve or increase that through automation and technology; indeed, this is in large part Amazon’s business model. So these two companies provide, indeed, a sizeable purchase, but they are fundamentally working companies that will contribute to Amazon’s business.

TechCrunch additionally noted that this is an indicator of how serious Amazon is about entering the groceries market. On this I agree, no doubt. Above and beyond being a working business, Whole Foods has more than $3bn in assets, mainly in more than 400 stores all around urban centres in the US. This kind of footprint takes a while to establish, and getting a big boost like this would immediately aid Amazon’s ambitions. That’s not all, though.

As a food retailer, Whole Foods has also a sizeable food distribution network, both contracting vendors to buy food but also the infrastructure and logistics to supply those same 400+ stores with fresh wares on a frequent basis. This, too, is non-trivial to build, as Tesco found out the hard way with Fresh & Easy. And, again, for Amazon, the Whole Foods purchase provides all of this and more.

As such, while the sheer size of the acquisition makes the previous tech acquisitions pale in comparison for Amazon, the Whole Foods one has certainly better immediate value, both on an ongoing basis, and when viewed as part of a plan to take over the food retail business in the US.